- Home

- Regina Marler

Queer Beats Page 3

Queer Beats Read online

Page 3

Ginsberg had helped his mother sell chickpeas to benefit Israel during Communist Party meetings in the 1930s. He had entered Columbia hoping to become a labor lawyer. It was inevitable, perhaps, that his verse should become political—especially after he found both his subject matter and his form in Howl—and perhaps also inevitable that in the end, his public life would undercut his writing. By the mid-1960s, Ginsberg’s political work would absorb far more of his time than his increasingly diffuse and oftendictated poems, and he would complain to Jane Kramer, his first biographer, that he talked about escaping to the woods to write for a year, and sometimes longed for “the simple, private pleasures of a homey Hindu kirtan or a sacred orgy among friends.”33 He gave his political energies and his grassroots organizing expertise variously to the Peace Movement, freedom of speech efforts, the fight to legalize marijuana, and a host of progressive causes, such as the dissemination of Buddhist thought in America.

Curiously, while Ginsberg is a gay icon, he was not necessarily considered a gay rights activist by others in the emerging movement. Randy Wicker, a New York activist and media campaigner, knew Ginsberg because they were both part of the five-member League for the Legalization of Marijuana. He credits Ginsberg with being out of the closet in the reactionary 1950s, and with writing Howl, “which was certainly liberating. However, he never was involved in the gay liberation movement with the one exception when he picketed the United Nations with me and The Homosexual League of New York protesting Castro’s incarceration of homosexuals in 1964.” 34

“Allen wasn’t considered a bona fide gay civil rights activist by those of us in the 1960s vanguard of our movement,” agrees Jack Nichols, who edited the first gay weekly newspaper in America, Gay. But his fame did draw attention to the small but historically pivotal uprising in Greenwich Village that began with a routine police raid of the Stonewall Inn on the night of June 27, 1969. Two nights later, as the street riot was dying down, Ginsberg visited the Stonewall and told a Village Voice reporter: “You know, the guys there were so beautiful. They’ve lost that wounded look that fags all had ten years ago.”

Ginsberg’s enduring contribution to the gay liberation movement is his visibility as an out gay man, as well as a body of work that celebrates gay male sexuality, from Howl to Straight Hearts’ Delight, a 1980 collection of his queer poems alongside writings by his lover, Peter Orlovsky, to a series of erotic poems on Neal Cassady. He made good use of his bad reputation, too, in coaching Vietnam-era protégés who were hoping to beat the draft: “Tell them you love them, tell them you slept with me.”

William Burroughs lacked the benevolent public persona of Allen Ginsberg, who could quell riots at poetry festivals by stretching his hands toward the audience and intoning “Ommmm.” A gray, spectral figure, dubbed “El Hombre Invisible” by the Spanish hustlers in Tangier, Burroughs dressed like a 1950s narcotics agent or a low-level spy. He was tight-lipped on first meetings, and in Paris practiced a technique of envisioning his visitors back outside his door, in the hallway. Almost always they got up to leave. The most intellectual of the Beat writers, he also believed in possession by evil spirits, thought control, and wish machines. His writings are exuberantly violent, with a strong strain of misogyny alongside his loathing of male effeminacy. In Mexico City in September 1951, he killed Joan Vollmer Burroughs, by then his common-law wife, in a drunken William Tell stunt with a handgun. All these are good reasons for his uneasy position in the gay literary canon. To further complicate appreciation of his work, he had a fully functioning Protestant horror of the flesh: a form of self-disgust that today we might call internalized homophobia if it didn’t flatten history into a tasteless wafer.

“Burroughs’s work appealed to the alienated,” says Ira Silverberg, a longtime friend and the coeditor of Word Virus, “whether they were queer or not. His queer audience is the smallest.” 35 Like Ginsberg, he did nothing to ingratiate himself with gay readers in particular. But those on the fringes—much further out than sexual orientation alone could put one—saw his vision as more daring and apocalyptic, both more surreal and, paradoxically, more realistic than either Ginsberg’s or Kerouac’s. He was the patron saint of junkies. When he rented his windowless basement apartment at 222 Bowery (“The Bunker”) in New York City in 1974, he learned there was a neighborhood drug dealer with the street name “Doctor Nova,” after his novel Nova Express. And though his thinking was progressive on many issues, like the 1980s “War on Drugs” and the environment, he was no kitten with respect to gun control or other “socialist” tendencies in government. Perhaps because, unlike Ginsberg, Burroughs didn’t embody a unified set of values, his impact on pop culture was still on the rise when the youth culture faded into the conservative 1980s. His later influence on gay liberation was oblique, coming through his refusal to succumb to the taming forces of the marketplace and his depictions of fantasy worlds in which gay sex and male–male bonding were less the exceptions than the rule.

Although the quest for authenticity led the Beat writers in different directions formally and thematically, their work shares a queer tension between violence and gentleness, between contrasting models of masculinity, between primitive faith and rational suspicion. In their lives as well as in their writings, they maintained porous boundaries between male camaraderie and sexual desire. There is a violent and self-destructive aspect to their physical indulgences: Kerouac was a cantankerous drunk who eventually killed himself with alcohol; Cassady died of exposure in Mexico in 1968 after mixing downers and alcohol; Burroughs shot his wife, alienated his alcoholic son, and lost many productive years to his drug addictions. But at its best, the Beat legacy is one of celebration, tenderness, sincerity, and spontaneity in life as in art. “There’s no doubt,” said Burroughs, “that we’re living in a freer America as a result of the Beat literary movement, which is an important part of the larger picture of cultural and political change in this country during the last forty years, when a four-letter word couldn’t appear on the printed page, and minority rights were ridiculous.”36

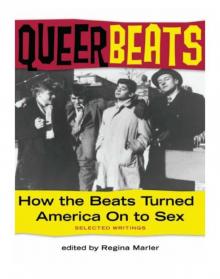

Queer Beats: How the Beats Turned America On to Sex brings together a diverse collection of primary and secondary texts that allow the Beat writers to be viewed from and through the perspective of their fluid sexuality. It is the first book of its nature. There is, of course, more queer and queer-ish Beats writing than could be included in any single volume, but I hope that Queer Beats provides a starting point for further reading and fresh insights.37

The three sections—The Road of Excess (Or, Saintly Sinners), Male Muses (Or, Sex without Borders), and Queer Shoulder to the Wheel—were originally conceived of as chronological, though this proved far too rigid a plan. Nevertheless, I’ve tried to pursue narrative threads where they occur. Emphasis is on the three principal Beats—Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs—together with their friends and lovers, but I include contributions by related figures on the queer Beat fringe, like Paul and Jane Bowles; gay poets John Wieners, Alan Ansen, and Harold Norse; Diane di Prima (though her bisexuality doesn’t figure in the orgy scene from Memoirs of a Beatnik included here); and poet/performer John Giorno, famous for founding Dial-a-Poem, starring in Andy Warhol’s first film, Sleep, and, in a post-Beat gesture of gratuitous candor, publishing the cock sizes of the writers and artists he’d had sex with. One of Giorno’s contributions here, “I Met Jack Kerouac For One Glorious Moment in 1958…,” comes from his unpublished memoir-in-progress.

In the spirit of the Beats, I’ve preserved all instances of unconventional spelling or grammar in the originals.

Regina Marler

San Francisco

April 2004

I.

The Road of Excess

(Or, Saintly Sinners)

A dvice for young artists is hopelessly contradictory, but almost no one would propose the kind of Dionysian abandon that the Beat writers relished in the early days of their friendship—on the streets and in the bars of New York City (fabled places like the San Remo, the Wes

t End Bar, the Cedar Street Tavern), and then on the various stops on the Beat circuit: Denver, San Francisco, Mexico City, Tangier, Paris. “The only people for me are the mad ones,” wrote Kerouac in the most famous lines of that ode to excess, On the Road, “the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn…”’38

“Mad” behavior was essential to the Beats, their first answer to the conformist ethos of the 1940s and 1950s. They cultivated—and applauded—a lack of inhibition: sex at a moment’s notice, with a hustler or a friend or a friend’s lover; sudden arrivals and departures; big arguments and reconciliations. To quiet a heckler at a Los Angeles poetry reading in 1957, Ginsberg stripped off his clothes. Their writing methods came to reflect their philosophies of life, with both Ginsberg and Kerouac adopting the Buddhist motto “First thought, best thought” as an argument for leaving their hastily written first drafts untouched. In “The Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” Kerouac advocated writing in a semitrance—like a jazz improvisation—and not allowing the conscious mind to censor after the fact. The rhythms should be free, following the breath and natural speech patterns. Punctuation was a straitjacket. A dash here and there would do. Nothing should be allowed to slow the flow of the authentic: “the best writing is always the most painful personal wrung-out tossed from cradle warm protective mind-tap from yourself.”

Luckily, Ginsberg and Kerouac were able to write while high, since they pursued, like Rimbaud, a systematic derangement of the senses. Even a dose of nitrous oxide at the dentist’s office could send Ginsberg into a state of “explicit Nirvana.” Dreams, visions, and drug trances could be equally inspiring. In November 1958, Ginsberg composed fiftyeight pages of his elegy for his mother, “Kaddish,” in a forty-hour burst, fueled by injections of heroin and liquid Methedrine, with the occasional Dexedrine tablet.39

In the panicked era of Reefer Madness, the Beats were amazingly sanguine about what they put into their bodies. There was little they wouldn’t try. An acquaintance once saw Joan Burroughs’s purse fall open on the floor. Pills of every color and shape spilled out. “There was a mystery about drugs,” wrote Michael McClure in Scratching the Beat Surface, “and they were taken for joy, for consciousness, for spiritual elevation, or for what the Romantic poet Keats called ‘Soul-making.’ ” Like their fluid sexuality, drug use was crucial to their work and their relationships, and fueled the constant crossing of boundaries that characterizes Beat writing. Both Ginsberg and Burroughs went as far as the Peruvian jungle to experience the hallucinogen yage (ayahuasca), a quest recounted in their book, The Yage Letters. When Timothy Leary began his investigations into LSD at Harvard University, Ginsberg was quick to volunteer. At a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on narcotics legislation in spring 1966, Ginsberg suggested that the senators look on acid as a “useful educational tool.” He described for them his peyote visions, and how yage helped him loosen up about women.

William Burroughs’s list was the most impressive. The opiates alone included “opium, smoked and taken orally, […] heroin injected in the skin, vein, muscle, sniffed (when no needle was available), morphine, dilaudid, pantopon, eukadol, paracodeine, dionine, codeine, demerol, methadone.” In Paris, Gregory Corso saw Burroughs fixing and asked if he could try it, as well. Soon Corso was addicted to “the white muse” and joined Burroughs in his daily attempts to score. Although Burroughs’s first novel was the narcotic autobiography Junky (1953), he didn’t write well on junk. In the grip of addiction, he would lock himself in his rented room and stare at his toes for weeks. Sometimes he would pay friends to execute “reduction cures,” hiding his clothes, policing the door, and doling out decreasing doses of his current habit to the naked, drug-sick patient. “You become a narcotics addict because you do not have strong motivations in any other direction,” Burroughs told an interviewer for Heroin Times. “Junk wins by default.”

In the 1960s, Burroughs informed a Paris Review interviewer that opiates were no help in writing, though marijuana had its uses. He tried to grow some at his New Waverley, Texas, farm in 1947, but the poorly cured product fetched almost nothing when he sold it in New York. The Beats used marijuana much as their Tangier friend Paul Bowles relied on majoun—not only as a key to the unconscious, but also as a gentle, daily adjustment to sobriety. The poster of Ginsberg marching in Sheridan Square wearing a homemade “Pot Is Fun” sign was ubiquitous in hippie households of the 1960s. Neal Cassady was the Johnny Appleseed of cannibis, distributing joints wherever he went. Kerouac became such an enthusiast that he declared, “War will be impossible when marijuana becomes legal. ”40 Although always a quick writer, Kerouac lavished a full three weeks in July 1952 on the experimental Dr. Sax, puffing weed around the clock. The novel’s loose, rolling, sex-steeped prose (which one biographer called “a madly sensible gibberish”) is evidence not only of his constant buzz, but of the Mexico City brothels he was frequenting for 36 cents a toss.

But before the romance of marijuana, there was the Benzedrine Inhaler, patented in 1932, which comes up so often in Beat memoirs that it is almost a minor character. A highly addictive treatment for asthma, Benzedrine came in the form of accordion-pleated, amphetamine-soaked papers tucked into a small vial. When Herbert Huncke couldn’t afford junk, he stumbled around Times Square in a Benzedrine haze. Joan Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, in what Kerouac would later call “a year of low, evil decadence” at their West 115th Street apartment, would crumple the papers into little balls and drop them into cups of coffee or Coke for a jittery all-day high. Kerouac wrote The Subterraneans on a three-day Benzedrine rush. Perhaps because he had the outlet of his writing, he seemed to handle the drug better than Joan Burroughs, who hallucinated a violent marriage for her downstairs neighbors, and once, in a panic, sent Ginsberg and Kerouac downstairs to break up a fight. They found the apartment empty.41

Had William Burroughs been a different sort of husband, he might have objected to Joan’s drug use, especially during her pregnancy with their son, Billy. But while Burroughs took his financial responsibilities as a family man very seriously, his marriage to Joan was an alliance of addicts. Only once did he hit her. Frustrated to see him back on junk, she had knocked a spoonful out of his hand. No one in the circle was sure how the enthusiastically straight Joan worked out her sexual relationship with Burroughs, but a few years later, when Ginsberg confronted him about his buying boys in Mexico when he was married to Joan, Burroughs snapped: “I never made any pretensions of permanent heterosexual orientation. […] Nor are we in any particular mess. There is, of course, as there was from the beginning, an impasse, and cross purposes that are, in all likelihood, not amenable to any solution.”42 Part of their arrangement seems to have been that Joan would not pressure Burroughs emotionally. A visitor to their Texas farm recalled Joan tapping on Bill’s door one night and asking if she could just lie in his arms for a while.

Joan devised a parenting philosophy of genial neglect, which allowed her to spend most of every day drunk or high. By 1951, the year of her death, she was walking with a limp from untreated polio. Her teeth had been blackened by drug use, and she had open sores on her arms. Unable to get Benzedrine in Mexico, she had switched to tequila, which she sipped all day. Lucien Carr and Allen Ginsberg visited her a few days before her death, while Burroughs was away with his boyfriend Lewis Marker. She took them on a wild, high-speed drive to Guadalajara to meet a pot connection. Both Lucien and Joan were drunk. Sometimes she steered while he lay on the floor working the gas pedal. A terrified Ginsberg cowered in the backseat with Joan’s children, shouting for her to stop. Joan’s death wish was obvious to Ginsberg. She was twenty-seven. A few days later at an acquaintance’s apartment, her husband, aiming his pistol an inch above the glass balanced on her head, shot her in the forehead from six feet away.

In “The Death of Joan,” Burroughs’s biographer and literary executor, James Grauerholz, has reconstruc

ted the event from the standpoint of each witness. There’s no evidence that Joan’s shooting was anything but a drunken stunt gone awry. But for the rest of his life, Burroughs would believe he had been possessed by evil at that moment, or that in some awful way Joan’s brain had drawn the bullet toward it. Whatever her role—psychic or otherwise—in the shooting, Joan’s decline and death were among the bitter consequences of the revelry that had begun so innocently in the mid-1940s. In a sense, she was the third casualty of the Beat search for supreme reality.43 As much as Howl is a celebration of excess—of crazy sex, drugs, self-assertion—it is also a lament for those, like her, who did not survive the times.

Allen Ginsberg

In Society

I walked into the cocktail party

room and found three or four queers

talking together in queertalk.

I tried to be friendly but heard

myself talking to one in hiptalk.

Queer Beats

Queer Beats