- Home

- Regina Marler

Queer Beats Page 4

Queer Beats Read online

Page 4

“I’m glad to see you,” he said, and

looked away. “Hmn,” I mused. The room

was small and had a double-decker

bed in it, and cooking apparatus:

icebox, cabinet, toasters, stove;

the hosts seemed to live with room

enough only for cooking and sleeping.

My remark on this score was under-

stood but not appreciated. I was

offered refreshments, which I accepted.

I ate a sandwich of pure meat; an

enormous sandwich of human flesh,

I noticed, while I was chewing on it,

it also included a dirty asshole.

More company came, including a

fluffy female who looked like

a princess. She glared at me and

said immediately: “I don’t like you,”

turned her head away, and refused

to be introduced. I said, “What!”

in outrage. “Why you shit-faced fool!”

This got everybody’s attention.

“Why you narcissistic bitch! How

can you decide when you don’t even

know me,” I continued in a violent

and messianic voice, inspired at

last, dominating the whole room.

1947

Herbert Huncke

On Meeting Kinsey

One afternoon when I was sitting in Chase’s cafeteria I was approached by a young girl who asked if she could join me. She was carrying several books in her arms and was obviously a student. “There’s someone who wants to meet you,” she told me.

I said, “Yes, who?”

“A Professor Kinsey.”

I had never heard of him and she went on to say, “Well, he’s a professor at Indiana University and he’s doing research on sex. He is requesting people to talk about their sex lives, and to be as honest about it as possible.”

My immediate reaction was that there was some very strange character in the offing who was too shy to approach people himself, someone who probably had some very weird sex kick and was using this girl to pander for him. But I sounded her down.

She must have known what the score was insofar as sex, but I didn’t know that. I didn’t want to shock her, but at the same time I wanted to find out exactly what the story was, so I questioned her rather closely about this man. I asked her why he hadn’t approached me himself, and she said, “He felt it would be better if someone else spoke with you. He has seen you around, and he thought you might be very interesting to talk to. I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll give you his name and number.” At that time he was staying in a very nice East Side hotel. “You can call him and discuss the situation with him.”

I had nothing else to do, and I said, “Well, I might as well find out what this is all about.”

I called Kinsey and he said, “Oh, yes, I’d like to speak with you very much.”

“What exactly is it you’re interested in?” I asked him.

“All I want you to do,” he said to me, “is tell me about your sex life, what experiences you’ve had, what your interests are, whether you’ve masturbated and how often, whether you’ve had any homosexual experiences.”

“That all you want?” I said.

“That’s all I want.”

“Well, I think it’s only fair to tell you,” I went on, “and I don’t want to be crude—but I do need money.”

He said, “I’d certainly be willing to give you some money. Would ten dollars be all right?”

“It certainly would.”

We went through a funny exchange. Kinsey wanted me to come up to his place, and I said, “No, I’d rather not do that. I’d rather meet you somewhere first.” I did not trust him yet. There was just something about the whole thing that sounded very offbeat to me. I arranged to have him meet me at a bar. “I’ll meet you at the bar, but I don’t drink,” he said. “But I’ll buy you a drink.”

“All right, fair enough.”

“I’ll know you when I see you,” he told me, “so you sit down and order yourself a drink and I’ll be there in a while.” We were to meet at a popular bar on [Times] Square […]

I didn’t have enough money to buy myself a drink, and I sort of kicked around in front of the place until I saw a cab pull up and a man get out. Kinsey had a very interesting appearance, strictly professorial. His hair was cut very short, slightly gray. He had a round face that was pleasant appearing, and he was dressed in a suit—obviously a conservative man, I thought.

He walked up to me and said, “I’m Kinsey. You’re Herbert Huncke. Let’s go in. You’d like to have a drink.”

I said, “Yes, I’d like to talk to you a few moments before we go to your hotel.” He again gave me much the same story the girl had, and he assured me that the only thing he was interested in was the discussion, though he did say he wanted to measure the size of the penis. He showed me a card which had a phallus drawn on it. He said he’d like to know the length of it when erect and when soft. Naturally, I was wondering when he was going to get to the point. It was all so strange, and I still did not quite believe him, but I thought, Well, hell, I might just as well go along with him and see what it’s all about.

As it turned out, it was a very delightful experience. As I started rapping to Kinsey about my sex life, I sort of unburdened myself of many things that I’d long been keeping to myself. For example, I’d always masturbated, all the way up until I kind of lost interest in sex altogether around the age of fifty. When I told others of my confessions to Kinsey they all said I was off my rocker, but I must say I was thankful by that time to get it out of my system. Sex had always played a prominent role in my life. I earned my living from sex at one time and have met all kinds of people, and heard of and had experiences with some very strange fetishes.

I told Kinsey most of these things. In Huncke’s Journal I describe an interesting experience I had as a young boy, and I spoke to him about this. It tells of a young fellow, about twenty years old, who, after telling me dirty stories and arousing me with pornographic pictures, suggested we go up into a building together. We did, and he suddenly startled me by dropping his pants. There he was with an erection. This thing looked gigantic to me, being eight or nine years old, because it just happened that it was dead in front of my face. I drew back but at the same time I say in all honesty that I was somehow interested. I felt no fear.

He said he wanted to feel me. I was embarrassed. Here was my tiny hunk of flesh and then this gigantic thing standing in front of me. It didn’t seem right somehow. Anyway, he did try and convince me that it would be a good idea if I’d allow him to put it up my rectum. I certainly drew the line at that, because I knew it’d be very painful. I assured him I wasn’t about to cooperate, and he didn’t press the issue. He proceeded to masturbate furiously and then he ejaculated. That was my first experience with anyone other than children my own age. This was the first thing I thought of when I began to masturbate. It would excite me. Instead of following the normal course and being pleased by visions of a little girl, I was attracted to this big phallus—a cock. It was quite an experience. I had never told anyone about it until I told Kinsey. It was this sort of thing that I unburdened myself of to this man.

As I continued to speak to him, he became so adept at his questioning and his approach that there was no embarrassment on my part, and I found myself relaxing. The one thing I could not supply him with was a size to my penis. He finally gave me a card and asked me to fill it out and send it to him later on, which, incidentally, I never did.44

William S. Burroughs

“Nobler, I thought, to die a man than live on, a sex monster…”

from QUEER

Lee and Allerton went to see Cocteau’s Orpheus. In the dark theater Lee could feel his body pull towards Allerton, an amoeboid protoplasmic projection, straining with a blind worm hunger to enter the other’s body, to breathe with his lungs, see with hi

s eyes, learn the feel of his viscera and genitals. Allerton shifted in his seat. Lee felt a sharp twinge, a strain or dislocation of the spirit. His eyes ached. He took off his glasses and ran his hand over his closed eyes.

When they left the theater, Lee felt exhausted. He fumbled and bumped into things. His voice was toneless with strain. He put his hand up to his head from time to time, an awkward, involuntary gesture of pain. “I need a drink,” he said. He pointed to a bar across the street. “There,” he said.

He sat down in a booth and ordered a double tequila. Allerton ordered rum and Coke. Lee drank the tequila straight down, listening down into himself for the effect. He ordered another.

“What did you think of the picture?” Lee asked.

“Enjoyed parts of it.”

“Yes.” Lee nodded, pursing his lips and looking down into his empty glass. “So did I.” He pronounced the words very carefully, like an elocution teacher.

“He always gets some innaresting effects.” Lee laughed. Euphoria was spreading from his stomach. He drank half the second tequila. “The innaresting thing about Cocteau is his ability to bring the myth alive in modern terms.”

“Ain’t it the truth?” said Allerton.

They went to a Russian restaurant for dinner. Lee looked through the menu. “By the way,” he said, “the law was in putting the bite on the Ship Ahoy [a bar] again. Vice Squad. Two hundred pesos. I can see them in the station house after a hard day shaking down citizens of the Federal District. One cop says, ‘Ah, Gonzalez, you should see what I got today. Oh la la, such a bite!’

“ ‘Aah, you shook down a puto queer for two pesetas in a bus station crapper. We know you, Hernandez, and your cheap tricks. You’re the cheapest cop inna Federal District.’ ”

Lee waved to the waiter. “Hey, Jack. Dos martinis, much dry. Seco. And dos plates Sheeska Babe. Sabe?”

The waiter nodded. “That’s two dry martinis and two orders of shish kebab. Right, gentlemen?”

“Solid, Pops.… So how was your evening with Dumé?”

“We went to several bars full of queers. One place a character asked me to dance and propositioned me.”

“Take him up?”

“No.”

“Dumé is a nice fellow.”

Allerton smiled. “Yes, but he is not a person I would confide too much in. That is, anything I wanted to keep private.”

“You refer to a specific indiscretion?”

“Frankly, yes.”

“I see.” Lee thought, “Dume never misses.”

The waiter put two martinis on the table. Lee held his martini up to the candle, looking at it with distaste. “The inevitable watery martini with a decomposing olive,” he said.

Lee bought a lottery ticket from a boy of ten or so, who had rushed in when the waiter went to the kitchen. The boy was working the last-ticket routine. Lee paid him expansively, like a drunk American. “Go buy yourself some marijuana, son,” he said. The boy smiled and turned to leave. “Come back in five years and make an easy ten pesos,” Lee called after him.

Allerton smiled. “Thank god,” Lee thought. “I won’t have to contend with middle-class morality.”

“Here you are, sir,” said the waiter, placing the shish kebab on the table.

Lee ordered two glasses of red wine. “So Dumé told you about my, uh, proclivities?” he said abruptly.

“Yes,” said Allerton, his mouth full.

“A curse. Been in our family for generations. The Lees have always been perverts. I shall never forget the unspeakable horror that froze the lymph in my glands—the lymph glands that is, of course—when the baneful word seared my reeling brain: I was a homosexual. I thought of the painted, simpering female impersonators I had seen in a Baltimore night club. Could I be one of those subhuman things? I walked the streets in a daze, like a man with a light concussion—just a minute, Doctor Kildare, this isn’t your script. I might well have destroyed myself, ending an existence which seemed to offer nothing but grotesque misery and humiliation. Nobler, I thought, to die a man than live on, a sex monster. It was a wise old queen—Bobo, we called her—who taught me that I had a duty to live and to bear my burden proudly for all to see, to conquer prejudice and ignorance and hate with knowledge and sincerity and love. Whenever you are threatened by a hostile presence, you emit a thick cloud of love like an octopus squirts out ink.…

“Poor Bobo came to a sticky end. He was riding in the Duc de Ventre’s Hispano-Suiza when his falling piles blew out of the car and wrapped around the rear wheel. He was completely gutted, leaving an empty shell sitting there on the giraffe-skin upholstery. Even the eyes and the brain went, with a horrible shlupping sound. The Duc says he will carry that ghastly shlup with him to his mausoleum.…

“Then I knew the meaning of loneliness. But Bobo’s words came back to me from the tomb, the sibilants cracking gently. ‘No one is ever really alone. You are part of everything alive.’ The difficulty is to convince someone else he is really part of you, so what the hell? Us parts ought to work together. Reet?”

Lee paused, looking at Allerton speculatively. “Just where do I stand with the kid?” he wondered. He had listened politely, smiling at intervals. “What I mean is, Allerton, we are all parts of a tremendous whole. No use fighting it.” Lee was getting tired of the routine. He looked around restlessly for some place to put it down. “Don’t these gay bars depress you? Of course, the queer bars here aren’t to compare with Stateside queer joints.”

“I wouldn’t know,” said Allerton. “I’ve never been in any queer joints except those Dumé took me to. I guess there’s kicks and kicks.”

“You haven’t, really?”

“No, never.”

Lee paid the bill and they walked out into the cool night. A crescent moon was clear and green in the sky. They walked aimlessly.

“Shall we go to my place for a drink? I have some Napoleon brandy.”

“All right,” said Allerton.

“This is a completely unpretentious little brandy, you understand, none of this tourist treacle with obvious effects of flavoring, appealing to the mass tongue. My brandy has no need of shoddy devices to shock and coerce the palate. Come along.” Lee called a cab.

“Three pesos to Insurgentes and Monterrey,” Lee said to the driver in his atrocious Spanish. The driver said four. Lee waved him on. The driver muttered something, and opened the door.

Inside, Lee turned to Allerton. “The man plainly harbors subversive thoughts. You know, when I was at Princeton, Communism was the thing. To come out flat for private property and a class society, you marked yourself a stupid lout or suspect to be a High Episcopalian pederast. But I held out against the infection—of Communism I mean, of course.”

“Aqui.” Lee handed three pesos to the driver, who muttered some more and started the car with a vicious class of gears.

“Sometimes I think they don’t like us,” said Allerton.

“I don’t mind people disliking me,” Lee said. “The question is, what are they in a position to do about it? Apparently nothing, at present. They don’t have the green light. This driver, for example, hates gringos. But if he kills someone—and very possibly he will—it will not be an American. It will be another Mexican. Maybe his good friend. Friends are less frightening than strangers.”

Lee opened the door of his apartment and turned on the light. The apartment was pervaded by seemingly hopeless disorder. Here and there, ineffectual attempts had been made to arrange things in piles. There were no lived-in touches. No pictures, no decorations. Clearly, none of the furniture was his. But Lee’s presence permeated the apartment. A coat over the back of a chair and a hat on the table were immediately recognizable as belonging to Lee.

“I’ll fix you a drink.” Lee got two water glasses from the kitchen and poured two inches of Mexican brandy in each glass.

Allerton tasted the brandy. “Good Lord,” he said. “Napoleon must have pissed in this one.”

“I was afraid

of that. An untutored palate. Your generation has never learned the pleasures that a trained palate confers on the disciplined few.”

Lee took a long drink of the brandy. He attempted an ecstatic “aah,” inhaled some of the brandy, and began to cough. “It is god-awful,” he said when he could talk. “Still, better than California brandy. It has a suggestion of cognac taste.”

There was a long silence. Allerton was sitting with his head leaned back against the couch. His eyes were half closed.

“Can I show you over the house?” said Lee, standing up. “In here we have the bedroom.”

Allerton got to his feet slowly. They went into the bedroom, and Allerton lay down on the bed and lit a cigarette. Lee sat in the only chair.

“More brandy?” Lee asked. Allerton nodded. Lee sat down on the edge of the bed, and filled his glass and handed it to him. Lee touched his sweater. “Sweet stuff, dearie,” he said. “That wasn’t made in Mexico.”

“I bought it in Scotland,” he said. He began to hiccough violently, and got up and rushed for the bathroom.

Lee stood in the doorway. “Too bad,” he said. “What could be the matter? You didn’t drink too much.” He filled a glass with water and handed it to Allerton. “You all right now?” he asked.

“Yes, I think so.” Allerton lay down on the bed again.

Lee reached out a hand and touched Allerton’s ear, and caressed the side of his face. Allerton reached up and covered one of Lee’s hands and squeezed it.

“Let’s get this sweater off.”

“O.K.,” said Allerton. He took off his sweater and then lay down again. Lee took off his own shoes and shirt. He opened Allerton’s shirt and ran his hand down Allerton’s ribs and stomach, which contracted beneath his fingers. “God, you’re skinny,” he said.

“I’m pretty small.”

Lee took off Allerton’s shoes and socks. He loosened Allerton’s belt and unbuttoned his trousers. Allerton arched his body, and Lee pulled the trousers and drawers off. He dropped his own trousers and shorts and lay down beside him. Allerton responded without hostility or disgust, but in his eyes Lee saw a curious detachment, the impersonal calm of an animal or a child.

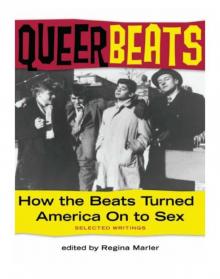

Queer Beats

Queer Beats