- Home

- Regina Marler

Queer Beats Page 5

Queer Beats Read online

Page 5

Later, when they lay side by side smoking, Lee said, “Oh, by the way, you said you had a camera in pawn that you were about to lose?” It occurred to Lee that to bring the matter up at this time was not tactful, but he decided the other was not the type to take offense.

“Yes. In for four hundred pesos. The ticket runs out next Wednesday.”

“Well, let’s go down tomorrow and get it out.”

Allerton raised one bare shoulder off the sheet. “O.K.,” he said.

Alan Ansen

Dead Drunk

In Memoriam

William Cannastra

1924-1950

For Winifred Gregoire

[Joan Burroughs was not the only member of the group to reach a violent end. There was, of course, Dave Kammerer, stabbed to death by Lucien Carr. Less well known was Bill Cannastra, a Harvard Law School graduate and queer prankster famous for heavy drinking and public stunts like running around the block naked. Cannastra had been trying to go straight when he died, having drunkenly attempted to climb out a subway window as it left the Bleecker Street station. A month later, in November 1950, Kerouac married Cannastra’s girlfriend, Joan Haverty.

It was in memory of Cannastra that Alan Ansen, perhaps the best “undiscovered” Beat poet, wrote “Dead Drunk.” Ansen was a friend to the Beats and secretary to W. H. Auden. Much of his openly gay poetry was published privately and distributed to friends, as James Merrill wrote, “at his own caprice.” Ansen is Rollo Greb in On the Road and A.-J. in William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch. In Tangier, he and Ginsberg worked six-hour days for two months to pull the manuscript of Burroughs’s Naked Lunch into shape. Ansen’s late collection Contact Highs (1989) was praised by Ginsberg for its “lunatic personal genius.”—ed.]

1

And the muddy glasses on the floor stinking of stale beer and smelly red wine

And the wreath of crisp dead ivy decorating the loft floor grave

And the senile remains of a rice and lamb hearts casserole on top of the great rusty stove

And a welter of theologians and script girls on the huge triple bed in the coma that confounds the just and the apathetic

And the garbage man sleeping alone on a little truckle bed in the corner

And the hum of the hi-fi nobody remembered to switch off

And the smashed Victrola record sprawling helpless at the feet of many accusing intact albums

And the indefatigable book review sucking a spent athlete on an off-centre divan

And the eyeglasses the empty bottles the books the draughtsman’s tools the blank sheets of paper the dead letters

And the host supine staring brown-eyed at the Everest ceiling of his overtenanted loft.

2

But once the ivy lived

Wrapping the warm brown naked body in tendrils of vivacious green

As it danced through gray and hostile streets

Joy to the world or at least

The moment’s festivity,

Pan.

For pipes a gramophone,

Glasses for hoofs keynote a face that entices all the others’ need

To be tender, hot, expansive to

Giveless mirages that crave

And crave in a vacuum

Graves.

Wild the gestures, liquid muscles, rippling eyes and a voice that is so alone with you in a room that sometimes even you aren’t there;

But all in vain.

The great god Pan is dead.

3

Let the sluices and sloshes of goblets and bottles lap high,

Let the air

Churn and gurgle with waves of poured liquids and vinous good feeling

As we reeling

From one bar to another in search of a brother get lost

In an early fall frost.

For in spite of our prancing and Corybant dancing as lamsters from care

The trains rattle by

And the choleric sky

As we lean out the moving subway car’s window

Toward the iron stanchion and its splattered future of our blobs of blood and brain

Has decreed and glaring still decrees that we die.

Herbert Huncke

Youth

When I was a schoolboy—age fifteen—living In what was conceded to be a respectable middle-class neighborhood in Chicago—I had my first encounter with love.

In the apartment building in which I lived with my mother, brother and grandmother (my mother and father had been divorced two years previously), there were several women who owned Chow dogs and they would pay me to take their dogs out for walks. This afforded me opportunity to make something of a show of myself—since Chows were quite fashionable—and as I considered myself at least personable in appearance, it rather pleased me to imagine that people seeing me walking along the Drive must surely think me the owner and certainly attractive with my pet straining at the leash. Frequently I would walk one of the dogs late in the evening and it was on such an occasion I first met Dick.

I had decided before returning home to stop by the neighborhood drugstore and as I was leaving someone spoke my name. I looked into the most piercing brown—almost black brown—eyes I had ever seen. They belonged to a man who at the time was in his late twenties—fairly well built—not too tall—with somewhat aquiline features and exceedingly black hair which he wore combed flat to his head. I learned later he was of Russian Jewish parentage.

I was very much impressed by his appearance and felt a strange sensation upon first seeing him which was to be repeated each time we met for as long as I knew him. I never quite got over a certain physical response to his personality and even now in retrospect I find myself conscious of an inner warmth.

As I was leaving the drugstore and after he had spoken my name and I had smiled and flushed, he commented that I didn’t know him but that a friend of his had spoken with me one evening about my dog and that I had given him my name, and he in turn had given it to him when they had seen me walking and he had asked if his friend noticed me. He then asked me if I would object to his accompanying me home so that we might become better acquainted. He gave me to understand that he wanted to know me. I was no end pleased by his attention and became animated and flirtatious.

We had a thoroughly enjoyable walk and from that point on I began seeing him fairly regularly. He was in the recording business and second in charge of a floor of recording studios in one of the large well-known buildings off Lake Shore Drive a short distance north of the Loop. He knew innumerable people in show business and I spent as much time hanging around the studio as could be arranged. Sometimes we would lunch together or stay downtown for dinner or go to a movie or he would take me along while he interviewed some possible recording star, and it was after some such instance at the old Sherman Hotel that he suggested since it was late I call home and ask permission to spend the night downtown. This I was anxious to do as I had long had the desire to sleep with him.

I was still rather green as to what was expected in a homosexual relationship, but I did know I was exceedingly desirous of feeling his body near mine and was sure I could be ingenious enough sexually to make him happy with me.

Actually I had but little experience other than mutual masturbation with others of my own age, and although I knew the word homosexual I wasn’t exactly aware of the connotations.

We spent the night together and I discovered that in fact he was nearly as ignorant as I and besides was filled with all sorts of feelings of guilt. We kissed and explored each other’s bodies and after both ejaculating fell asleep in each other’s arms.

This began a long period in which he professed deep love for me and on one occasion threatened to throw acid in my face should he ever discover me with someone else.

The affair followed the usual pattern such affairs follow and after the novelty wore off I became somewhat bored, although it appeased my vanity to feel I had someone so completely in my control. Had anyone threatened my suprema

cy I would have gone to great lengths to eliminate them from the situation.

About this time it was necessary for him to make a business trip to New York, and when he returned he was wearing a Persian sapphire ring which he explained he would give to me if I would promise to stay away from some of the people and places I had lately been visiting. I promised to do this and considered the ring mine.

One evening we had dinner in a little French restaurant we frequented, and, while eating, a very handsome young man joined us whom Dick introduced as Richard, who was attending classes at the University of Chicago and was someone he had met recently thru some mutual acquaintance. We sat talking and suddenly I was startled to see the ring on Richard’s finger.

Richard was considerably younger than Dick and really very beautiful. He was blond, with icy blue eyes—innocent and clear. He was very interested in life and people and kept bombarding us with questions—about our interests, the theater, music, art, or whatever happened to pop into his head. He laughed a good deal and one could feel a sense of goodness about him. He was obviously attracted to me and asked permission to call me on the phone so that we might make arrangements to see each other. I complied and began making plans about how to get the ring away from him—after all I felt the ring was mine—and I wanted it.

And so it happened that I succeeded in twisting one of the few really wondering things that occurred when I was young into a sordid, almost tragic experience which even now fills me with shame.

As I have already said—Richard was good. There was no guile in his makeup and he offered his love and friendship unstintingly. It was he who first introduced me to poetry—to great music—to the beauty of the world—and who was concerned with my wants and happiness. Who spent hours making love to me, caressing and kissing me on every part of my body until I would collapse in a great explosion of beauty and sensation which I have never attained in exactly the same way with anyone since. He truly loved me and asked nothing in return but that I accept him—instead of which I delighted in hurting him and making him suffer in all manner of petty ways. I would tease him or refuse him sex or call him a fool or say that I didn’t want to see him. Sometimes I would tell him we were finished, thru, and not to call me or try and see me, and it was after one such episode on a beautiful warm summer night—when I had agreed to see him again if he would grant me a favor—I asked for the ring and he gave it to me.

The next day I visited Dick at the studios and—with many gestures and words of denunciation—flung the ring at him, telling him that we were finished and that anyway he wasn’t nearly as amusing as Richard—and that maybe or maybe not I’d continue seeing Richard—and that in fact he bored me and I only felt sorry for him—and that I would never be as big a fool over anyone as he was over me—and besides my only reason for knowing him at all was so that I could get the ring.

Dick became enraged and began calling me foul names which he sort of spit at me and pulled from his desk drawer a pistol. He was waving it in front of my face and at the same time telling me how cruel and heartless I was and that he could forgive the stupidity of my actions in regard to himself but that the harm I was inflicting on Richard was more than he could stomach and I would be better dead. Suddenly he started shouting—“Get out—get out—I never want to see you again.” By this time I was shaking and almost unable to stand and stumbled out of his presence.

The following day in the mail I received a letter from Richard containing a poem—that read almost like this—

A perfect fool you called me.

Perchance not as happy in my outlook on life and people as you—

Yet in like manner—playing the role of a perfect fool—

Gave me a sort of bliss—

You in all your wisdom—will never know.

Shortly after receiving the letter I called Richard and asked to see him. He refused to see me and at that time I would not plead. A strange thing had happened to me—I had become aware—almost overnight—of the enormity of my cruelty—and I was filled with a sudden sense of loneliness—which I have never lost—and I wanted Richard’s forgiveness.

Richard never forgave me and I have only seen him once since the time he gave me the ring—and that was only long enough for him to tell me—he was trying to forget he had known me.

It was a cold winter day.

Nor did I ever speak with Dick again. Not so many years ago—I read in the paper—he is dead.

1959

William Burroughs

“I don’t mind being called queer…”

from a letter to Allen Ginsberg, April 22, 1952

[The publishers of Junkie had requested a biographical preface from Burroughs. Ginsberg was serving as Burroughs’s agent, and had sold the manuscript to his friend Carl Solomon at Ace Books.—ed.]

Now as to this biographical thing, I can’t write it. It is too general and I have no idea what they want. Do they have in mind the—“I have worked (but not in the order named) as towel boy in a Kalamazoo whore house, lavatory attendant, male whore and part-time stool pigeon. Currently living in a remodelled pissoir with a hermaphrodite and a succession of cats. I would rather write than fuck (what a shameless lie). My principal hobby is torturing the cats—we have quite a turnover. Especially in Siameses. That long silky hair cries aloud for kerosene and a match. I favor kerosene over gasoline. It burns slower. You’d be surprised at the noises a cat can make when the chips are down”—routine, like you see on the back flap? Please, Sweetheart, write the fucking thing will you? PLUMMM. That’s a great big sluppy kiss for my favorite agent. Now look, you tell Solomon I don’t mind being called queer. T. E. Lawrence and all manner of right Joes (boy can I turn a phrase) was queer. But I’ll see him castrated before I’ll be called a Fag. That’s just what I been trying to put down uh I mean over, is the distinction between us strong, manly, noble types and the leaping, jumping, window dressing cocksucker. Furthecrissakes a girl’s gotta draw the line somewheres or publishers will swarm all over her sticking their nasty old biographical prefaces up her ass.

Norman Mailer

“Burroughs may be gay, but he’s a man…”

Burroughs may be gay, but he’s a man. What I mean is that the fact that he’s gay is incidental. He’s very much a homosexual but when you meet him that’s not what you think of him. You might think about him as a hermit, a mad prospector up in the mountains who’ll shoot you if you come to his cabin at the wrong time. Or you can see him as a Vermont farmer who’s been married to his wife for sixty years, and the day she dies someone says, “I guess you’re going to miss her a lot, Zeke,” and he says, “No, never did get to like her very much.” So that he’s got all those qualities, and on top of it all he is very much a homosexual, but that’s somehow not the axis. He also has that way that certain people in society act, very formal, which is a defense against indiscreet inquiry, when let’s say they’ve been put in jail for twenty years and they come out, and you can never refer to it in their presence, you wouldn’t dream of it.

Gore Vidal

“We owed it to literary history...”

from PALIMPSEST

[On the night of August 23, 1953, Vidal and Kerouac, who knew each other slightly, met at the San Remo with Burroughs. From there, the three went on to Tony Pastor’s, a lesbian bar. Kerouac drunkenly swung on a lamp-post afterward, “a Tarzan routine that caused Burroughs to leave us in disgust,” Vidal recalled. Kerouac suggested that he and Vidal get a room somewhere, and with misgivings—Vidal preferred younger men, and Kerouac, at 31, was three years older—Vidal agreed. In The Subterraneans, Kerouac gave an otherwise factual, homo-censored account of the evening. Vidal supplied the missing details in a 1994 meeting with Allen Ginsberg, and in his memoir, Palimpsest.—ed.]

At the nearby Chelsea Hotel, each signed his real name. Grandly, I told the bemused clerk that this register would become famous. I’ve often wondered what did happen to it. Has anyone torn out our page? Or is it still hidden away in the du

sty Chelsea files? Lust to one side, we both thought, even then (this was before On the Road), that we owed it to literary history to couple.

I remember that the bathroom was near the entrance to a large double room. There was no window shade, so a red neon light flickering on and off gave a rosy glow to the room and its contents. Jack was now in a manic mood: We must take a shower together. To my surprise, he was circumcised. Under the shower, for a moment, he rewound himself to the age of about fourteen and, for an instant, I saw not the dark slackly muscled Jack but blond Jimmie,45 only Jimmie was altogether more serious and grown-up at fourteen than Jack…

I have just recalled Tennessee [Williams]’s aversion to sex with other writers or, indeed, with intellectuals of any kind. “It is most disturbing to think that the head beside you on the pillow might be thinking, too,” said the Bird, who had a gift for selecting fine bodies attached to heads usually filled with the bright confetti of lunacy.

Where Anais [Nin] and I were incompatible—chicken hawk meets chicken hawk—Jack and I were an even more unlikely pairing—classic trade meets classic trade, and who will do what?

“Jack was rather proud of the fact that he blew you.” Allen sounded a bit sad as we assembled our common memories over tea in the Hollywood Hills. I said that I had heard that Jack had announced the momentous feat to the entire clientele of the San Remo bar, to the consternation of one of the customers, an advertising man for Westinghouse, the firm that paid for the program Studio One, where I had only just begun to make a living as a television playwright. “I don’t think,” said the nervous advertiser, “that this is such a good advertisement for you, not to mention Westinghouse.” As On the Road would not be published until 1957, he had no idea who Jack was.

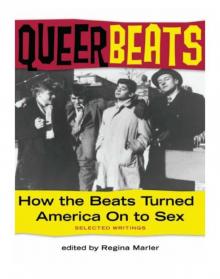

Queer Beats

Queer Beats